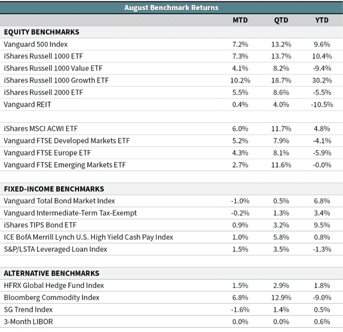

After the sharp drawdown in February and March, equities have posted gains for five straight months. Larger-cap U.S. stocks gained 7.2% in August and have surged 36.5% over the last five months (Vanguard 500 Index), their largest five-month gain since 1938 (using the S&P 500/Ibbotson). Smaller-cap U.S. stocks gained 5.5% in August (iShares Russell 2000 ETF). Smaller caps are still negative on the year (down 5.5% year to date), whereas larger caps are nearing double-digit gains.

The often-highlighted divergence between growth and value stocks continued to favor growth during the month. Larger-cap U.S. growth stocks gained 10.2% in August and are now up over 30% this year. On the other hand, larger-cap U.S. value stocks returned 4.1% last month but are still down 9.4% in 2020.

Returns were also positive in foreign stock markets; however, they trailed U.S. equities during the month. Developed international stocks rose 5.2% in August, as they continue to dig out of their year-to-date hole—now down just 4.1% in 2020 (Vanguard FTSE Developed Markets ETF). Emerging-market (EM) stocks were the laggard among the main equity asset classes—gaining 2.7% in August (Vanguard FTSE Emerging Markets ETF). For the year to date, EM stocks are now flat.

Treasury rates at the longer end of the curve inched up during the month. U.S. core bonds notched their first loss since March. Core bonds quietly lost 1% during August, their first loss in excess of 1% since early 2018 (Vanguard Total Bond Market Index). Credit spreads were largely unchanged during the month.

Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell’s virtual Jackson Hole speech was noteworthy during the month. Fed officials had already signaled plans to keep interest rates pinned near the zero bound through at least the end of 2022. Furthermore, in his August speech, Powell announced updates to the Fed’s Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy.

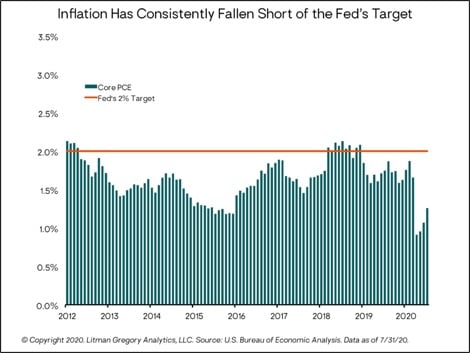

Back in 2012, the central bank put out its first statement on “longer-run goals” and in it they adopted an inflation target of 2%. Since then the economy has largely undershot this target (see chart below). In an update to this statement, the committee now “seeks to achieve inflation that averages 2 percent over time, and therefore judges that, following periods when inflation has been running persistently below 2 percent, appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time.” It essentially means that policymakers are now more willing to tolerate an overshoot on inflation.

Skeptics might wonder why the Fed would raise the inflation bar when it hasn’t been able to hit their target in the first place. Except for a couple of years leading up to the 2008 financial crisis, inflation has not been over 2% in the last two decades. But the change in framework has as much to do with the Fed’s other mandate: promoting maximum employment. As Minneapolis Fed president Neel Kashkari noted in a recent interview (Bloomberg’s Odd Lots podcast), the tightening that began in 2015 was a mistake that was predicated on a misreading of the labor market. The Fed thought we were at full employment and that they needed to hurry up to raise rates before inflation came. Obviously, inflation did not come despite employment reaching levels that were previously thought to be inflationary. The mistake wasn’t missing their inflation target, it was slowing the recovery in the labor market due to fears that inflation was around the corner. By targeting higher inflation, the Fed is basically signaling they will hold off on hiking interest rates the next time the labor market is strong. With the unemployment rate around 10%, it could be a long time until the Fed moves rates from current levels.

—OJM Group Investment Team (09.14.20)