What History Can Tell Us About Investing During The COVID-19 Crisis

Tensions have been high since March for all investors, including aesthetic physicians. For the first time ever, many medical practices closed, decimating revenue and personal income. On top of this has come a stock market downturn and extreme market volatility, where many physician investors have seen years of retirement savings wiped out in a matter of months, or even weeks.

“What Should I Do?”

All of this leads to a common but crucial question for many physicians: “What should I do?” In this article, we will answer this question, at least in terms of personal finances and investing. In fact, as you may have gleaned from the title of the article – the answer is simple, but often not easy. Stay the course.

When we say, “stay the course,” this does not mean that we are encouraging investors to do nothing. Ideally, in conjunction with a trusted financial professional, there are many tactics that can be taken to protect and build family finances during this crisis. These include revisiting retirement/financial models (focusing on cash reserves and potential cuts in spending) and repositioning the portfolio with a possible rebalance of asset classes to their strategic benchmarks. Some aesthetic physicians may need to raise cash for spending purposes, while others may allocate further to equities, seeing lower stock prices as a buying opportunity for the long term. These tactics may all make sense and should be guided by rational planning.

In other words, what “stay the course” really means is to stick with your long-term financial and investment plan and avoid getting caught up in emotional decision making (i.e., fear). Actions driven by fear – or the urge to just “do something” – often feel right when watching hard-earned savings quickly evaporate but can often lead to disastrous long-term financial consequences.

Timing the Market

The opposite of staying the course is to try to time the market. In essence, market timing means selling assets when one thinks the market will continue to decline and then buying back in when it feels safe that the market has bottomed out. This may sound enticing in theory. In practice, however, the evidence is overwhelming that most investors diminish their long-term returns trying to do so. They are more likely to chase the market up and down, and get whipsawed, buying high and selling low. Market timing, while tempting, involves getting two nearly impossible decisions right: when to sell and when to get back in.

Data from the Past 60 Years

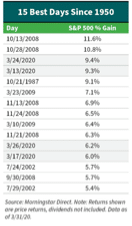

The table to the first table on the right shows that the 15 best days for the S&P 500 (through March 31, 2020) all occurred within bear markets, not bull markets as you might expect. In other words, the best days to be in the market have been when it is hardest to remain invested or tempting to get out of the market and wait for better days. Looking at these dates, you will find the who’s who of dark times for the stock market: the 2008 financial crisis, the dot-com crash, the Black Monday crash of 1987. A handful of these best days even happened in the first quarter of 2020, during the onset of the COVID-19 crisis.

By trying to miss the worst days, investors are very likely to miss the best days. Let’s examine how detrimental this can be.

The Extraordinary Damage of Missing A Few Days

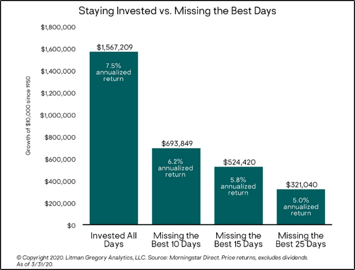

Missing just the 10 best days (out of more than 17,500 trading days since 1950) has a significant long-term effect on a portfolio. For example, an investor who invested $10,000 in the S&P 500 in 1950 would have gained 7.5% annualized and finished with a portfolio value of more than $1.5 million (as of March 31, 2020) if they had remained fully invested (not including dividends). However, the portfolio value for an investor that missed the 10 best days is much, much lower—just shy of $700,000.

Now it is unlikely an investor will miss only the best days if they attempt to time the market. They might also be able to miss some of the historically bad days. However, the cautionary tale of attempting to time the market is the same: There can be an enormous cost to pay if the market swings to the upside while you’re on the sidelines. It would take a crystal ball to get in and out of the market perfectly, particularly since it needs to be done in short order given the market’s best and worst days tend to cluster close to one another. Investors should also be aware of the tax implications associated with attempts to time the market, which can often make the tactic even more painful.

Conclusion

While owning stocks on historically bad days can be unsettling, staying the course is the best plan of action during periods of severe market stress. Doctors, like all investors, would do well to remember the investing adage, “Time in the market beats timing the market,” and avoid emotional decisions regarding their finances. Ideally, working with a trusted and experienced financial professional can help keep the physician on the right path.